Публикации

Round 9 Report from Chess.com Isle of Man International

(сайт Chess.com Isle of Man International, 29.10.2018)

Round 9 Report

John Saunders reports: the 2018 Chess.com Isle of Man International was won by Radoslaw Wojtaszek of Poland after a play-off match with Arkadij Naiditsch of Azerbaijan. The two players led going into the last round and drew their ninth round game to finish on 7/9 while none of the four players on 6/8 managed to win in order to tie with them. They each take home a cheque for £37,500 with Wojtaszek also receiving a further £500 for winning the blitz play-off. The initial two-game blitz was tied on 1-1 but Wojtaszek chose White in the Armageddon game and duly won. Seven players finished on 6½: Vladimir Kramnik, Alexander Grischuk (both Russia), Hikaru Nakamura, Jeffery Xiong (both USA), Wang Hao (China), Gawain Jones (England) and Baskaran Adhiban (India).

Arkadij Naiditsch drew their round 9 game before returning to play-off for the prestige and a further £500 pot (photo: John Saunders)

Husband and wife Radoslaw Wojtaszek and Alina Kashlinskaya carried off both the major prizes at the tournament (photo: John Saunders)

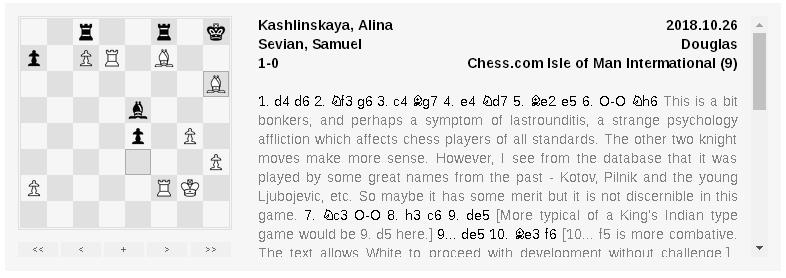

The overall winner was upstaged by his wife Alina Kashlinskaya in the last round. For one thing it was her 25th birthday. Secondly, she only needed to sit down at her board to complete her requirement for a GM norm. Her next goal was the top women’s prize of £7,000. Her main rival for this was Alexandra Kosteniuk who was soon on top against Sundararajan Kidambi, so Alina would need to win herself in order to secure the prize on her own. This she proceeded to do in trenchant style, beating the talented young US GM Samuel Sevian and making light of the (almost) 200 rating point difference which she conceded to him.

Alina Kashlinskaya, with her GM norm safel secured, sets about winning the top women's prize against Samuel Sevian (photo: John Saunders)

... to be continued...

OK, this is the continuation of the round nine report. It’s been delayed a bit by (a) my need to sleep and (b) a little local difficulty with the hotel wifi, which is now thankfully sorted out. Thank you for bearing with me.

Back at round nine: the two round eight leaders, Radek Wojtaszek and Arkadij Naiditsch, were naturally paired in the ninth round, with the Azerbaijani GM having White. The pundits, cynics that we are, rather expected them to split the loot with an early repetition or a breeze through well-known moves to move 30. The two players were not quite as unsubtle as that, however, and Naiditsch even messed with our heads a little by disdaining a repetition opportunity on move 15 – one, incidentally which MVL and Carlsen took advantage of when drawing in the Norway Chess tournament in Stavanger last June. Wojtaszek then exited opening theory by moving his knight back to the odd square a7. A couple of moves later Naiditsch gave up a pawn in order to set up a heavy piece pin against this knight and things were starting to look interesting. Naiditsch then gave up a piece to make the pin even more deadly but Wojtaszek had a handy way to defend at the cost of a hole in his kingside. But this was also a hole in our hopes of a sole winner as Naiditsch, a piece for two pawns down, found he had little option than to use the hole to force perpetual check. So a thirty-move game but one with a reasonable portion of cut and thrust without being exactly thrill-a-minute stuff.

Jeffery Xiong and Gawain Jones both had excellent tournaments and finished in a seven-way tie for 3rd place (photo: John Saunders)

That left three boards in play where there were players who could still match the 7/9 score made by Wojtaszek and Naiditsch. On board two a decisive result for either Jeffery Xiong and Gawain Jonescould see them through to a share of the money. Xiong had White and the game began with an indeterminate queen’s pawn opening in which all four bishops were fianchettoed. On move 14 Jones diverged from the game Xiong-Izoria from the last US Championship, then following a game from the French Team Championship for a while longer. Xiong took the initiative, advancing pawns first on the kingside and later on the queenside, and the result of the latter plan was an isolated pawn in Black’s camp which Jones thought better to jettison in order to seek activity rather than defend statically. This proved sensible and in time he was able to restore material equality and draw. Thus both players remained on the second score group, and could probably look back on the best tournament of their lives. Jeffery Xiong has remarkable self-confidence, not to mention, ability, for a young man who only turns 18 a couple of days after the tournament. He should go far. And Gawain Jones also had a great tournament, winning games with White and proving unbeatable with Black despite some horrendous positions. He has always been a creative, original player but he now seems to have added a high level of resilience to his arsenal.

A rare defeat for Maxime Vachier-Lagrave while Alexander Grischuk was on his best form (photo: John Saunders)

On board three Alexander Grischuk received an upfloat to play Maxime Vachier-Lagrave, which meant that only the Frenchman had the opportunity to reach the leaders’ score. He opened with his favourite Najdorf Sicilian, with a view to a counterattacking position from which he could mount a challenge for a win. Grischuk was game too, giving up a pawn, but before long the queens came off and equality was established. Later a position was reached where the pawn deficit had switched to MVL but he had compensation in the shape of two bishops against two knights. This game also feature a moment when a repetition seemed likely to happen but Grischuk it was who disdained it. Later there was another double shuffle but again Grischuk was just teasing his opponent. Earlier he even retreated into a corner with his knight and MVL might have done better to pen him in there. Allowing the knight into play could have been the turning point as Grischuk’s pawn structure was better and his three connected pawns on the queenside rolled forward. Grischuk’s b-pawn reached b6 and on move 59 MVL probably made his fatal miscalculation, playing 59...Bf5 instead of the necessary check 59...Rd8+ to keep the white king at bay. White advanced 60.b7 and suddenly everything worked for White and the game was over. That meant the end of MVL’s hopes of sharing first prize though of course he wouldn’t have done so had he secured a half point.

Alexander Grischuk looks serious at the board but he was on top wisecracking form in the studio afterwards (photo: John Saunders)

Grischuk, now doubt elated at beating such a strong opponent, was as astute as he was witty in his post-game interview with Fiona Steil-Antoni. He provided us with one stat, that it was the first decisive classical game between the two players, having previously drawn a dozen or so games. He alluded to MVL’s initial mistake being 38...Re6 which allowed Grischuk to exchange two pawns, but with MVL’s pawn being of the more dangerous passed variety. Then there was a typical flash of humour: “I have the feeling that the tournament is just starting but it's already ending." Interviewer Fiona Steil-Antoni laughed and replied “I don't feel that at all!” – an allusion to the long hours that she and the rest of the webcasting team work. Grischuk acknowledged this with a joke: “That's because you work every day – unlike me! Most of my games were non-existent. I had a couple of very easy wins with White and I had these very short draws with Black.”

Grischuk then drew our attention to his game with MVL being the one and only pairing between two of the tournament’s top ten players in the entirety of the tournament. “I don’t know why it has happened and it’s very strange. There are 45 possible pairings between those top people – and [we’ve had] 1 out of 45... maybe it’s because this tournament is getting stronger year by year and still there are only nine rounds. Maybe that was fine when the tournament was much weaker, but it just feels a little bit strange. Nothing happens – and then it’s finished! It’s like having a 100m distance in cycling or Formula One over one kilometre.” With Fiona’s next question about how he enjoyed his time here, Grischuk gave us a glimpse of the typically mischievous, irreverent side to his personality: “[I enjoyed it] very much. But even the name – island of Man” (pulls a face) “you know, these days everything is so tolerant, politically correct, asexual – and here we have island of Man!” with a gesture indicating surprise. “It’s an amazing feeling to be here!” he said, with a big smile for the giggling Fiona.

Going back to Grischuk’s point about there having been only the one pairing between the leading players out of a possible 45: I consider this the inherent unfairness of Swiss pairing rules, which favour strong players. Cast your mind back a year and we had a pairing between two top ten players in the very first round – thanks to the random pairings. My case rests.

Wang Hao tried hard to beat the former world champion but Vishy Anand defended stoutly (photo: John Saunders)

Wang Hao, on board four, also had a shot at sharing in the big money but to do so he would have to beat Vishy Anand. One thing was for sure that Wang would play to the bitter end. The queens came off early in a QGD but Wang Hao kept pressing throughout the game, with better placed pieces and slightly less vulnerable pawns. It was good, honest struggle with no major error found by engines, and a fine defensive effort by the former world champion.

Play-Off

So that was first place tied up, literally, between Wojtaszek and Naiditsch and the bulk of the money decided at that point with the £50,000 first prize and £25,000 second prize added together and divided equally between them – £37,500 each. There was also a play-off to decide who would lift the trophy at the prizegiving, and take another £500. Given the relative smallness of the extra money hanging on the play-off compared with that at other events, I don’t suppose there was as much pressure on them, but anyway, the play-off was played. They were blitz games and, given that they came not long after a nine rounds of the toughest classical chess imaginable, not of the highest quality, but they were very entertaining for the crowd.

Arkadij Naiditsch lost game 1 but hit back to level in this, the second game (photo: John Saunders)

Wojtaszek won the first after a seesawing struggle in which he shed two points for an initiative, then the second was similar but with Naiditsch winning to send the mini-match to Armageddon. Wojtaszek won the toss for colours and chose to play White, with 5 minutes to his opponent’s 4, with 5 second increments at the back end of the game, but with a draw counting as a Black success. A third sub-standard but exciting game ensued and White triumphed again. Thus Wojtaszek increased the family earnings by another £500 on top of the £37,500 he had already won and the £7,000 his wife had taken. Not a bad haul for nine days’ chess, and well deserved. Credit also to Arkadij Naiditsch who would also not have been unhappy with his take-home pay.

Arkadij Naiditsch resigns the Armageddon, making Radoslaw Wojtaszek the 2018 Isle of Man winner (photo: John Saunders)

Arkadij Naiditsch resigns the Armageddon, making Radoslaw Wojtaszek the 2018 Isle of Man winner (photo: John Saunders)

Alexei Shirov vs Vladimir Kramnik: two old rivals renew hostilities while Pavel Eljanov awaits his opponent (photo: John Saunders)

Third place was shared by seven players. We’ve already accounted for four of them but there were also three winners amongst the players who started the round on 5½. One was Vladimir Kramnik, whose pairing with Alexei Shirov reminded us of the shenanigans of 1998/99 when Shirov qualified for a title match with Garry Kasparov but didn’t get the shot at the title because funding couldn’t be raised for the match. Later funding was found for a match between Kasparov and the young Kramnik, much to Shirov’s chagrin since he maintained, and with good reason, that the challenge should have been his. The rest, as they say, is history; Shirov has had some successes since but he has since slipped to a rating which is around 100 adrift of his one-time usurper. In the game, a Ruy Lopez, Kramnik had the tiniest of initiatives from an early stage up to around move 30 when Shirov made a serious error on move 36 which cost him one pawn and then another. The rest was a technical job for Kramnik. A pretty good tournament in some ways for Kramnik – certainly a lot better than in 2017 when he lost two of his first three games – but his slow start with two draws meant he never got to grips with the other challengers and was never quite in the running for the first prize.

Unfazed by the trauma of his loss in round eight, Hikaru Nakamura finishes the tournament on an upbeat (photo: John Saunders)

In the background of my photo of Shirov-Kramnik above you can see Pavel Eljanov looking round for his absent opponent, Hikaru Nakamura. One caption writer, citing this photo, joked as to whether Eljanon was hoping Nakamura might not turn up after his traumatic loss of the previous day but, rather like another famous American player at the Sousse Interzonal in 1967, Nakamura had not done with the tournament yet, and he duly arrived and defeated his opponent. Nakamura put pressure on his opponent with 22.e5, and this may have induced the mistake 24...Bd6, with White having a lengthy tactic to regain a pawn and take positional control. He then won a pawn and Black tried a knight sacrifice in order to reach a drawn rook versus rook and knight endgame. But Nakamura still retained a pawn and eventually constructed a position in which he could secure one of Black’s and win. This carried Nakamura into the group of players in the second score group.

Not a good day at the office for Mickey but joy for Baskaran Adhiban (photo: John Saunders)

The final member of the magnificent seven on 6½ was Baskaran Adhiban who beat Mickey Adams. Adams was White and played a Bb5 Sicilian, giving up a pawn for some play and the strong likelihood that it would be regained anyway. This duly came about and a level rook and knight endgame resulted. Normally you would stake the Bank of England on Mickey holding a draw in such a position but he went a bit too passive around move 35 and then relied on giving up a piece to reach a five pawns versus knight and three pawns endgame to save himself. It became one of those familiar endgames where saving moves are available but gradually diminish in number compared with losing ones. On move 54 there was only one saving move left in the position and unfortunately Mickey didn’t find it. Credit to Adhiban, he found a couple of not so easy moves to exploit Mickey’s slip and that was game over. A grand result for Adhiban but two straight losses represented a disappointing end to the tournament for England’s number one after doing pretty well previously.

Alexandra Kosteniuk made the last move of the congress (barring the tie-break) beating Sundararajan Kidambi (photo: John Saunders)

The winner of the women’s first prize, as we have already seen was Alina Kashlinskaya with a remarkable 6/9. Remarkable for either sex, in fact: the next lowest rated player to her 2447 on that score group was Daniel Fridman who is rated 2600, and she finished with more points than five players rated 2700+. The next best score for a woman player was Alexandra Kosteniuk with 5½/9. Alexandra finished well with 2½/3, including two GM scalps, and she will have achieved her objective, which was to get into shape for the upcoming Women’s World Championship. In third place was the evergreen Pia Cramling who recovered strongly from a slow start.

Chess Prodigies

The thing that really strikes you when you are present at the venue is the performance of the formidable squad of Indian juniors, plus the equally strong German player Vincent Keymer, and one or two others. ‘Formidable’ is perhaps not quite the right word as that makes them sound overly serious or nerdy: they are actually just normal, amiable, energetic kids when they are around the place. Even when they sit down to play they are still just kids – perhaps just a tad fidgety compared to adult players but definitely not in any deliberately distracting way, it is just that it is impossible for kids of that age to sit stock still for hours at a time. They look in all directions as well as at the board, not needing the pieces to look at as they can see the position in their heads – I remember British prodigies who did this and there was never any malice in it.

Boys Just Wanna Have Fun: Vincent Keymer plays bullet chess with ageless big kid IM Lawrence Trent (photo: John Saunders)

But the maturity of the chess they play, their energy and their ability to maintain their concentration and focus over the long hours of top-level competition chess: I never cease to marvel at it. Part of their talent is their self-confidence and self-possession and they are not intimidated by reputations or the sheer physical size of some of their opponents (it’s worth bearing in mind that guys like Kramnik and Shirov are seriously big as well as seriously good at chess). It was a joy to watch them play and interact with some of the best players in the world without any debilitating sense of awe.

Bringing this back to the final round, there was a disappointment for Vincent Keymer as he failed to gain the draw he needed against Emil Sutovsky to get his GM title but of course it will come along soon enough and his trajectory is way beyond the GM title.

Vincent Keymer: close but no GM norm this time - it won't be long (photo: John Saunders)

Gukesh, Praggnanandhaa and Nihal Sarin: an amazing trio of Indian prodigies (photo: John Saunders)

Three of the top Indian juniors, Gukesh, Praggnanandhaa and Nihal Sarin, found themselves sitting next to each other in the final round, which was a nice photo op for me, speculating that they will be the nucleus of the Olympiad team before long. That’s assuming that more Indian prodigies don’t come along; their numbers seem to double year on year. They lined up against Wesley So, Le Quang Liem and Zoltan Almasi, with just the one of them, Nihal Sarin, escaping without defeat against the American – but that was a very classy result, of course.

Prizegiving

To the winners, the spoils, and the big winners were as already reported here. The best news was that there is money to hold the tournament again in 2019, tinged with disappointment that it will not be at the much-loved Villa Marina due to a clash with other booked events. But tournament organiserAlan Ormsby has other venues in mind so we’ll be here again next year as a venue and on dates yet to be notified. Hope you’ve enjoyed reading these reports as much as I’ve enjoyed writing them, and I too hope to write and take pictures for you all again next year.

Arkadij Naiditsch received his share of the 1st/2nd prizes (£37,500) from tournament organiser Alan Ormsby (photo: John Saunders)

Radoslaw Wojtaszek had the honour of making the winner's speech at the prizegiving (photo: John Saunders)

Alina Kashlinskaya receives her GM certificate from chief arbiter Peter Purland (photo: John Saunders)

Soumya Swaminathan gets her IM norm certificate from Peter Purland (photo: John Saunders)

In his speech Radek Wojtaszek paid a glowing tribute to help given him by Vishy Anand (photo: John Saunders)

"What have we done, Radek?": Alina Kashlinskaya probably can't believe the family success (photo: John Saunders)